Last summer was hot in Alaska.

How hot was it, you ask?

Well, last summer was so hot, salmon were literally cooking themselves in the rivers.

Bad joke? Perhaps. While you won’t find river-boiled salmon on the menu at your local seafood restaurant anytime soon, it’s a fact that last July, as Alaska and much of the Arctic experienced near-record warmth, the water temperature in some Alaskan rivers reached an unfathomable 82 degrees Fahrenheit (28 degrees Celsius). The abnormally warm waters led to mass salmon die-offs.

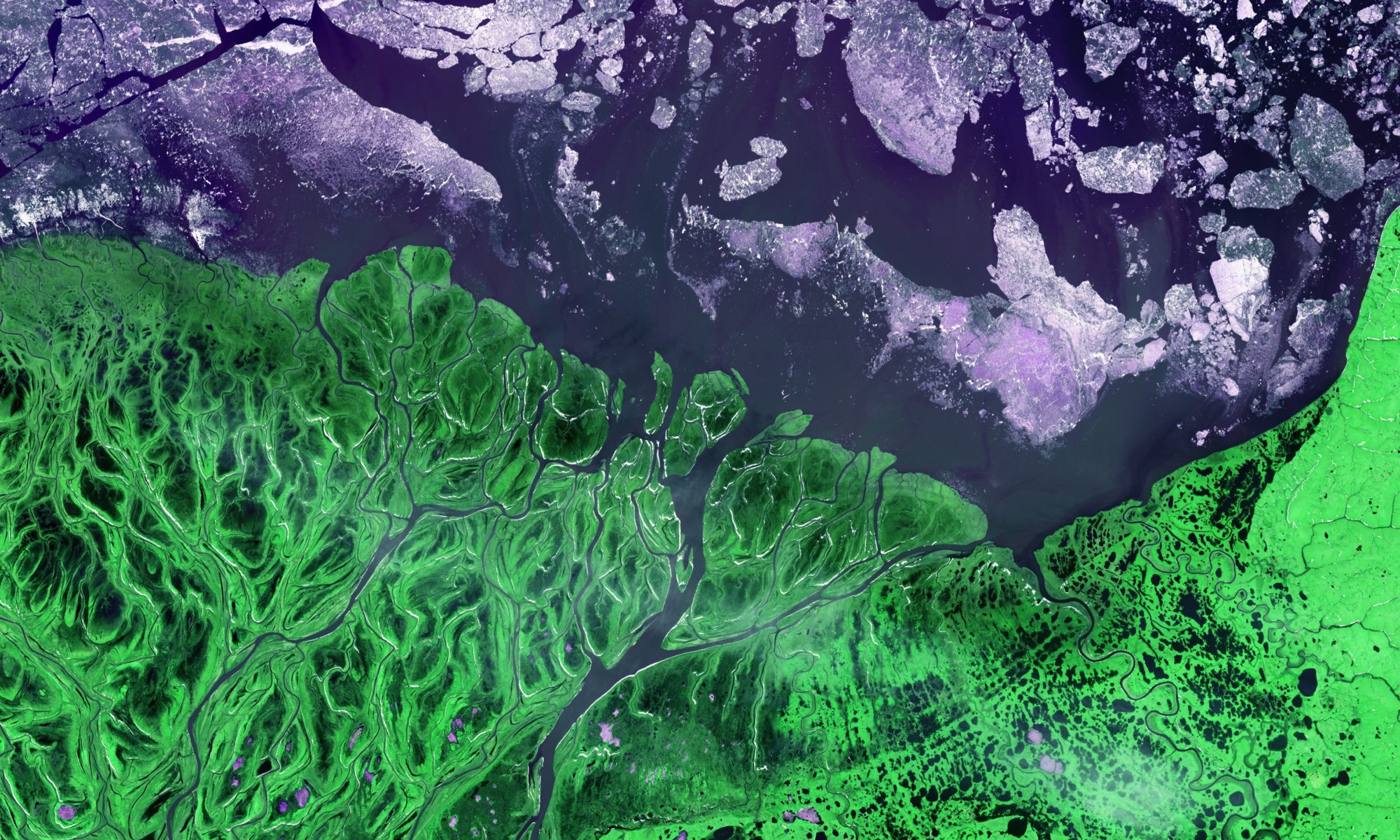

Sadly, the fate of the simmering salmon, while exaggerated, stems from a disturbing reality. As the Arctic warms three times faster than the rest of our planet, this excess heat is taking an increasingly severe toll on Arctic ecosystems and Earth’s climate.

Ask Chip Miller. The NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory atmospheric scientist has spent much of the past decade crisscrossing Alaska and Canada as a lead scientist on two NASA airborne field campaigns: The Carbon in Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE) and the Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE).

Read on to explore how airborne remote sensing helps Arctic and Boreal scientists understand permafrost, wildfires, caribou, methane hotspots, biome shifts and much more…

Chip Miller, ABoVE airborne lead scientist, shares his experiences from thousands of meters up, and GEODE/ABoVE science lead Scott Goetz describes a northward march of shrubs.