Drones are an important addition to scientists’ toolkits for measuring global change, concludes new study in Environmental Research Letters

A scientist’s toolkit for understanding Arctic vegetation change (primarily driven by Arctic “greening”) has often relied on two main tools: field work and satellite imagery.

Field work is highly detailed – researchers meticulously estimate vegetation cover, measure height, and weigh plants to determine their mass. Scientists come away with detailed and accurate data, but it comes at a price. This work is tedious and time consuming. And, in an area as remote as the Arctic, simply getting to field sites is costly, often involving lengthy flights or grueling hikes across challenging terrain.

This work is extremely important because of the level of detail it contains – this data is as close to “true” as we can get. However, the scope is small. Field plots are often about the size of a coffee table. Consider the vastness of the Arctic and you can see why a few coffee tables scattered across the tundra do not capture the full picture.

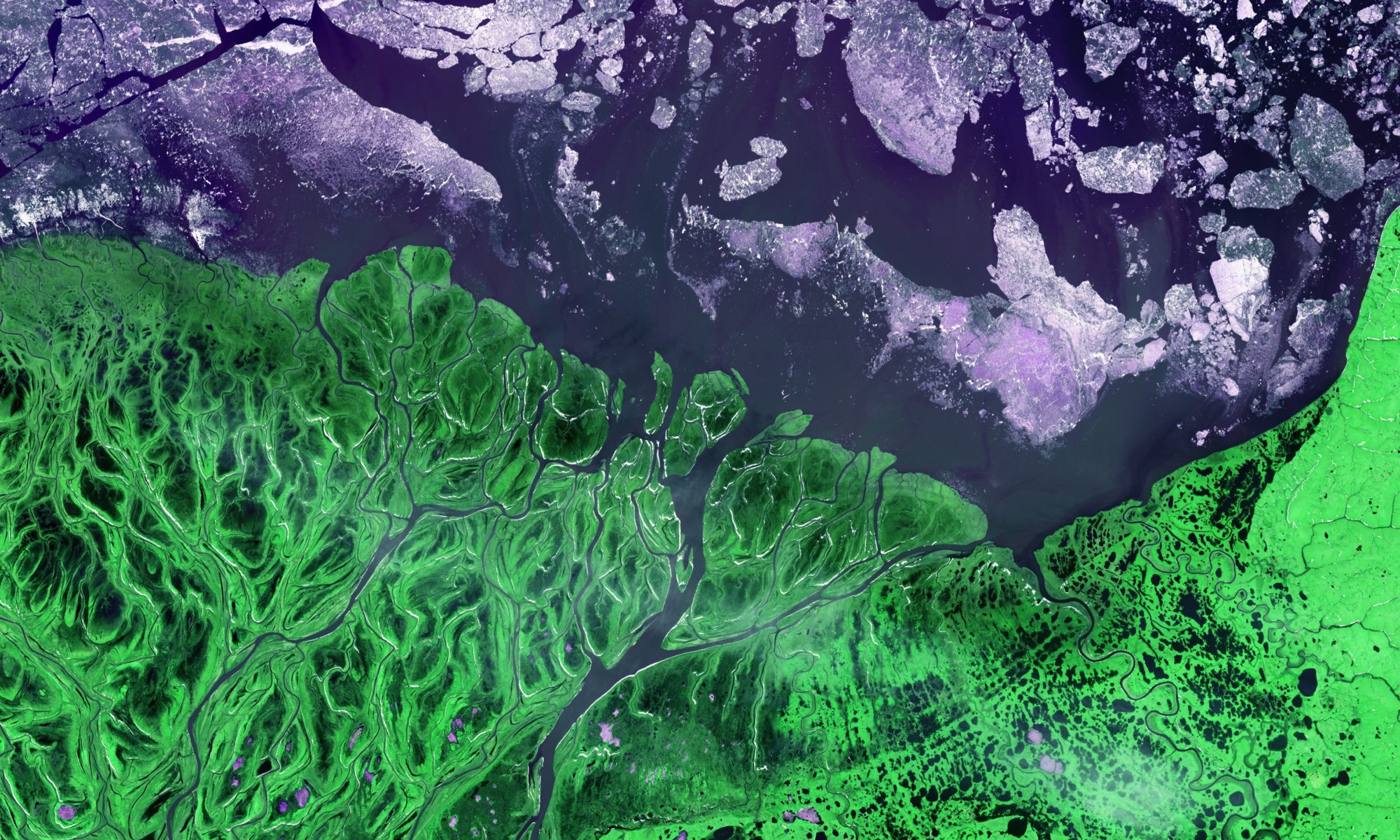

At the other extreme is satellite imagery. Using images beamed back to Earth from satellites that orbit constantly, scientists can look at pictures anywhere in the Arctic dating back to the 1980s. This tool provides excellent coverage, but it comes at the price of detail. Pixels from satellite imagery “are maybe the size of Manhattan,” says Jeff Kerby, ecologist at Aarhus University in Denmark. These pixels can tell scientists which areas have gotten greener (or browner), but cannot provide much detail about the mechanisms that cause the greening.

It is a big leap from detailed data the size of a coffee table, to a single “greenness” value representing an area the size of Manhattan. “You end up with that gap in between,” said Andrew Cunliffe, research fellow at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom. In a new study in Environmental Research Letters, Cunliffe and his colleagues suggest drones might be the key to bridging this gap in scale and scope.

Drones are relatively portable and inexpensive. Scientists can bring them to the field with them and collect imagery as they conduct field work. The result is an expanded view of the field site, the size of several football fields as opposed to a single coffee table. And the resolution is impressive too – scientists can obtain imagery with pixels as small as a single centimeter. This makes drones an important ‘middle man’ between field work and satellite imagery. Scientists can use drone imagery to peer inside a single satellite imagery pixel for more detail.

What’s more, new technology allows researchers to stitch together images from drone flights to create 3D reconstructions of sites. This adds a third dimension of information, not usually afforded by satellite imagery. These structural metrics, along with measures of greenness provide “an unprecedented opportunity to monitor changes both in tundra greenness and canopy structure such as canopy height and aboveground biomass,” according to Alemu Gonsamo, a remote sensing vegetation and climate change scientist at McMaster University in Canada.

GEODE lab members are also excited about drone potential. We in the GEODE lab know that “Scale is one of the key issues with remote sensing,” as summed up nicely by GEODE lead Scott Goetz.

“There is tremendous potential for the sort of work that they have done to improve our understanding for what these changes in tundra greenness mean, why they’re happening, and how the Arctic might change in the future,” adds GEODE assistant research professor Logan Berner.

Read more about how Arctic researchers are using drone technology, or head straight to the science.

And check out the GEODE lab’s new drone fleet!